Why Squatters Don't Marry

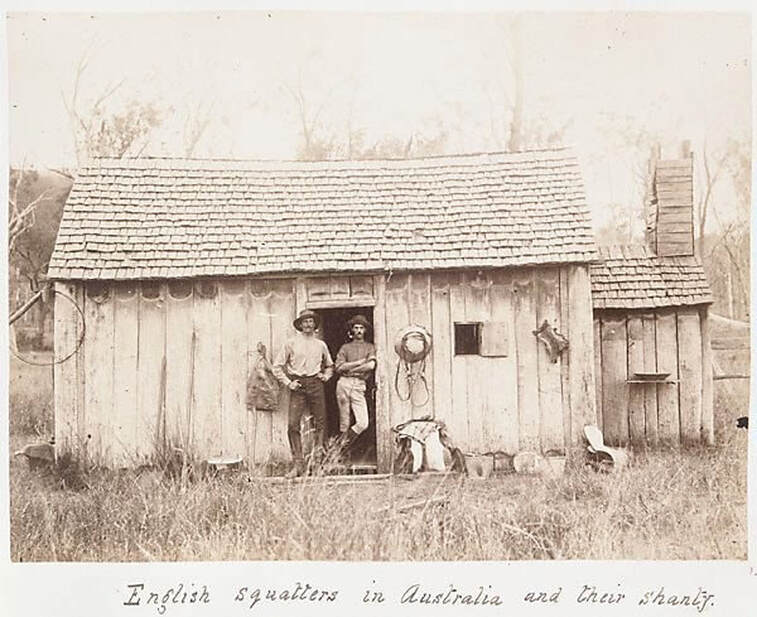

This 1870 article discusses reasons why squatters were marrying late in life. It helps explain why none of Malcolm McLaran's three sons were married prior to Donald's wedding in 1879, 26 years after the family's arrival in Queensland.

It appears there was no shortage of sexual partners, though: some related, others "in the trade".

17 Jun 1870 The Brisbane Courier

WHY SQUATTERS DON’T MARRY

The projected marriage of one of our fortunate squatters with the amiable and accomplished daughter of a certain gentleman of high position in the sister colony suggests the question, "Why don't squatters marry?' It has often been asked why men foremost in physical strength, with good mental powers, energy far above the average of colonists, do not marry? Is it the extent of the pioneer squatter's leasehold possessions that makes him feel that his worldly cares are so overwhelming, and of a nature so peculiar that he dare not ask a lady to share them with him? This is barely sufficient to account for the celibacy of so many squatters, because whether a squatter holds a huge, medium, or small area, to find celibacy the rule among them, and marriage the exception.

The pioneer squatter makes up his mind when he first enters on bush life to do or die - to realise a fortune or to lose one. It is not until he is fairly in harness that he finds his task likely to tax all his energies. The grazier's avocation is midway between the large squatter or leaseholder and the small freeholder. Many of these graziers, however, have large freehold estates with ring fences, also country houses which, if they do not actually vie with mansions owned by squires in Great Britain or Ireland, are replete with all the comforts which Australia Felix can supply.

Our Australian democracy has made the pioneer squatters' tenure so insecure - dependent as it is on a vote of the Legislature - as to effectually debar the squatter in the wilderness from becoming a Benedict. He cannot safely marry for a number of years after he has sat down in the far bush, because he does not know how Dame Fortune will treat him. He soon finds that he has before him such an uphill game that he is not warranted to ask any female, his equal in the social scale, to share his early difficulties. To make such a home as he would like to bring his wife to would take him many years, at a time when his moments are golden, because he is trying to sow the seeds of future success. Nothing is certain in the pioneer's affairs while his tenure is insecure.

A Ministry antagonistic to the pastoral pioneers, probably so from a want of proper knowledge on the subject, may, at any time, dash away all hope from the expectant squatter, because the Land Act gives him no legal right to a renewal of his lease even under the most stringent regulations as to improvements. The Act states that the Ministry may grant the Crown pastoral tenant a renewal of his lease under certain conditions, but it gives him no right to demand a renewal when he has faithfully earned it. Now, if the tenure of the leaseholder depended upon the lands so leased to him being required for freehold settlement, the very vastness of the interior would protect the pioneer, and he could marry early. If, in its wisdom, the Legislature lowered the price of land, and did not prohibit the squatter therein from buying large quantities, he would then be on the road to Hymen - whether or not to happiness. No Act of Parliament could settle this question.

It takes a pioneer squatter generally fifteen to twenty years’ hard work in the wilderness to make him feel safe in a pecuniary sense. Supposing he begins his task at thirty, he is forty-five or fifty years old ere he is eligible for marriage; a squatter of the latter age has little steel left in him, though he may originally have been of good material. If he should then marry and become a father, the chances are against his living to see his firstborn become an adult. Neither are the children likely to have the vis of the father. Dowager mothers acting in their daughters' interest consider successful squatters as very eligible men, and as a rule they are so viewed in a pecuniary light. A successful squatter is pretty sure to turn out a good husband, because he has arrived at an age when his expectations are reasonable. He is sure to select a youthful bride - possessing considerable personal attractions, accomplished, and of charming disposition. The sacrifice is mainly on the part of the wife, and it is no insignificant compliment to the fair sex when the pioneer squatter, after fifteen or twenty years' of toil, lays all at the feet of a young and accomplished woman.

At the age of fifty or so, he, with his fifty or hundred thousand pounds, secures such a wife, whereas, when he was twenty-five or thirty years of age, though only possessed of a tithe of the money, he might have welded probably with advantage to both. But what of the unsuccessful squatters - the men who do not draw prizes. They are dead sea men - upon them fortune has not smiled. Enterprising mothers with marriageable daughters, follow, as a rule, the example of the fickle goddess. "Leah was tender-eyed, but Rachel was beautiful and well favored.” Bible critics say "that Leah possessed eyes like the dove" - we shall not attempt to settle the point, but the price which Labun placed upon beautiful and well-favoured Rachel, is proof that she was considered the belle of the family, and as such was only fit for the wealthiest lover. The unsuccessful pioneer and ex-squatter would probably have to be content with Leah, the tender-eyed.

It is a matter for regret in a national sense that our pioneer squatters cannot see the way to marrying early in life, because it is very desirable that we should have descendants from these men equal to their fathers in physique, in perserverance, boldness, and all the loading and best features that belong to mankind. For this reason in particular we wish that the franchise had been extended to females, who would early in our history have settled the question of squatters' tenure. Women, well knowing that it is not good for man to be alone, would clearly have seen that it was wrong to enforce celibacy on so many of our marriageable young men in the Australian wilds. The wife of the pioneer would have soothed his sorrow, and, speaking from personal observation, in some cases would have snatched from the lonely pioneer-squatter the bottle which sent him before his turn into eternity.

Comment

This article describes Donald McLaran very accurately, except he lived long enough to see most of his nine children grow to be adults. Their ages were spread between 32 and 14 when he passed away... shortly before two of them tragically joined him in the Dalby Monumental Cemetery..

It appears there was no shortage of sexual partners, though: some related, others "in the trade".

17 Jun 1870 The Brisbane Courier

WHY SQUATTERS DON’T MARRY

The projected marriage of one of our fortunate squatters with the amiable and accomplished daughter of a certain gentleman of high position in the sister colony suggests the question, "Why don't squatters marry?' It has often been asked why men foremost in physical strength, with good mental powers, energy far above the average of colonists, do not marry? Is it the extent of the pioneer squatter's leasehold possessions that makes him feel that his worldly cares are so overwhelming, and of a nature so peculiar that he dare not ask a lady to share them with him? This is barely sufficient to account for the celibacy of so many squatters, because whether a squatter holds a huge, medium, or small area, to find celibacy the rule among them, and marriage the exception.

The pioneer squatter makes up his mind when he first enters on bush life to do or die - to realise a fortune or to lose one. It is not until he is fairly in harness that he finds his task likely to tax all his energies. The grazier's avocation is midway between the large squatter or leaseholder and the small freeholder. Many of these graziers, however, have large freehold estates with ring fences, also country houses which, if they do not actually vie with mansions owned by squires in Great Britain or Ireland, are replete with all the comforts which Australia Felix can supply.

Our Australian democracy has made the pioneer squatters' tenure so insecure - dependent as it is on a vote of the Legislature - as to effectually debar the squatter in the wilderness from becoming a Benedict. He cannot safely marry for a number of years after he has sat down in the far bush, because he does not know how Dame Fortune will treat him. He soon finds that he has before him such an uphill game that he is not warranted to ask any female, his equal in the social scale, to share his early difficulties. To make such a home as he would like to bring his wife to would take him many years, at a time when his moments are golden, because he is trying to sow the seeds of future success. Nothing is certain in the pioneer's affairs while his tenure is insecure.

A Ministry antagonistic to the pastoral pioneers, probably so from a want of proper knowledge on the subject, may, at any time, dash away all hope from the expectant squatter, because the Land Act gives him no legal right to a renewal of his lease even under the most stringent regulations as to improvements. The Act states that the Ministry may grant the Crown pastoral tenant a renewal of his lease under certain conditions, but it gives him no right to demand a renewal when he has faithfully earned it. Now, if the tenure of the leaseholder depended upon the lands so leased to him being required for freehold settlement, the very vastness of the interior would protect the pioneer, and he could marry early. If, in its wisdom, the Legislature lowered the price of land, and did not prohibit the squatter therein from buying large quantities, he would then be on the road to Hymen - whether or not to happiness. No Act of Parliament could settle this question.

It takes a pioneer squatter generally fifteen to twenty years’ hard work in the wilderness to make him feel safe in a pecuniary sense. Supposing he begins his task at thirty, he is forty-five or fifty years old ere he is eligible for marriage; a squatter of the latter age has little steel left in him, though he may originally have been of good material. If he should then marry and become a father, the chances are against his living to see his firstborn become an adult. Neither are the children likely to have the vis of the father. Dowager mothers acting in their daughters' interest consider successful squatters as very eligible men, and as a rule they are so viewed in a pecuniary light. A successful squatter is pretty sure to turn out a good husband, because he has arrived at an age when his expectations are reasonable. He is sure to select a youthful bride - possessing considerable personal attractions, accomplished, and of charming disposition. The sacrifice is mainly on the part of the wife, and it is no insignificant compliment to the fair sex when the pioneer squatter, after fifteen or twenty years' of toil, lays all at the feet of a young and accomplished woman.

At the age of fifty or so, he, with his fifty or hundred thousand pounds, secures such a wife, whereas, when he was twenty-five or thirty years of age, though only possessed of a tithe of the money, he might have welded probably with advantage to both. But what of the unsuccessful squatters - the men who do not draw prizes. They are dead sea men - upon them fortune has not smiled. Enterprising mothers with marriageable daughters, follow, as a rule, the example of the fickle goddess. "Leah was tender-eyed, but Rachel was beautiful and well favored.” Bible critics say "that Leah possessed eyes like the dove" - we shall not attempt to settle the point, but the price which Labun placed upon beautiful and well-favoured Rachel, is proof that she was considered the belle of the family, and as such was only fit for the wealthiest lover. The unsuccessful pioneer and ex-squatter would probably have to be content with Leah, the tender-eyed.

It is a matter for regret in a national sense that our pioneer squatters cannot see the way to marrying early in life, because it is very desirable that we should have descendants from these men equal to their fathers in physique, in perserverance, boldness, and all the loading and best features that belong to mankind. For this reason in particular we wish that the franchise had been extended to females, who would early in our history have settled the question of squatters' tenure. Women, well knowing that it is not good for man to be alone, would clearly have seen that it was wrong to enforce celibacy on so many of our marriageable young men in the Australian wilds. The wife of the pioneer would have soothed his sorrow, and, speaking from personal observation, in some cases would have snatched from the lonely pioneer-squatter the bottle which sent him before his turn into eternity.

Comment

This article describes Donald McLaran very accurately, except he lived long enough to see most of his nine children grow to be adults. Their ages were spread between 32 and 14 when he passed away... shortly before two of them tragically joined him in the Dalby Monumental Cemetery..

|

1879 Clara Eversden on her wedding day

|

Jun 1878 “Bush goddess” on the Moonie!

27 Jun 1878 Queensland Times MOONIE RIVER (FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT) I will give a hint to unmarried ladies at and about Brisbane (you see we have the right pronunciation up here) and Ipswich, how to get rid of an unwelcome suitor. There is a young lady on the Moonie, "beautiful exceedingly," of course, and most of the young stockmen, when not literally breaking their necks in the bush after cattle, are metaphorically breaking their necks after this bush goddess. One of them was pressing his suit in the energetic style which prevails amongst the Moonie youths, whether after calves or after wives. The young lady was not "willin’ ". Did she murmur out that she loved him as a brother, but no farther? Did she say it was not a case of "Two souls with but a single thought - two hearts that beat as one?" Not much. She handed him a turnip - a hint which the forlorn swain took, and getting outside of whoever's horse he was riding, he "vamoosed the ranche," disappeared in "those vast solitudes and awful cells" for which the Moonie is so renowned, and howled out his sorrows to the scrub bulls, who bellowed in unison. By-the-bye, 'twas an awful sell for the victim. (This is another "goak.") Comment Surely the bush goddess had to be Clara Eversden? |