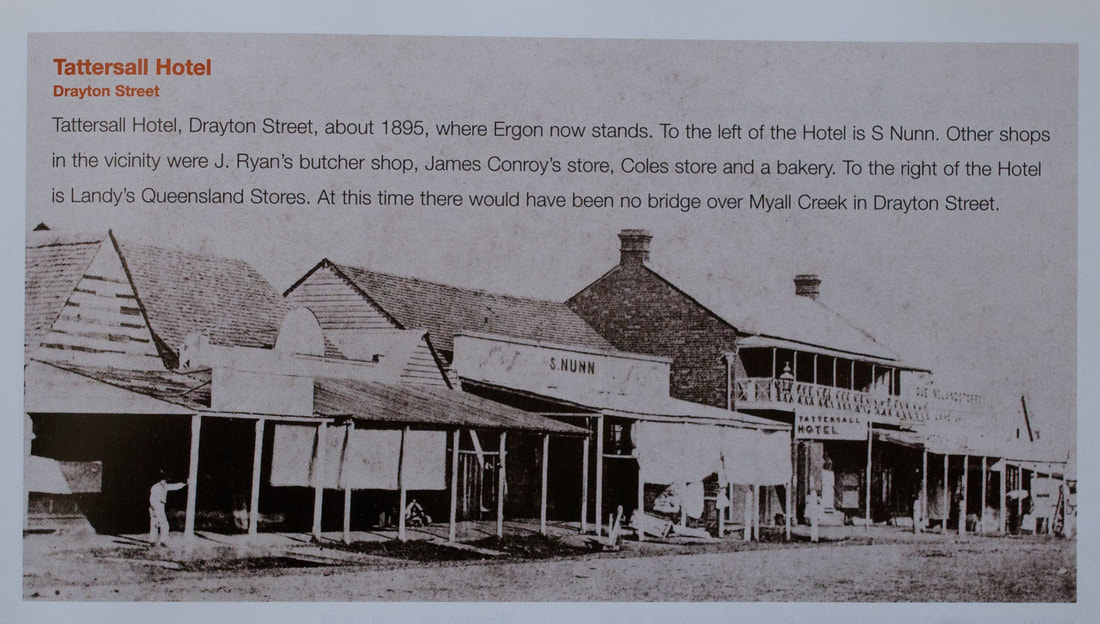

Tattersall Hotel - the scene of the 1874 Constable Skelly incident

1874 - Two separate cases: Police officers charged with assault

On 27 Apr 1874, in separate assault charges, two policemen were tried in the same session of the Western District Court in Dalby

It is possible that McLaran and Dockrill met for the first time in court that day and a common bond of resentment towards the authorities may have been cemented. It is also possible the two men met 10 years earlier - 1864 at Greenbank.

Perhaps this possible courthouse may have led to the 1879 marriage of Donald McLaran and Clara Eversden?

- Case 1 - Constable Skelly was charged with assaulting a Dalby publican. This involved Donald McLaran.

- Case 2 - Constable Balfour was charged with assaulting William Dockrill at Tartha.

It is possible that McLaran and Dockrill met for the first time in court that day and a common bond of resentment towards the authorities may have been cemented. It is also possible the two men met 10 years earlier - 1864 at Greenbank.

Perhaps this possible courthouse may have led to the 1879 marriage of Donald McLaran and Clara Eversden?

|

2 Mar 1874 Committal Hearing: Constable Thomas Skelly

7 Mar 1874 The Queenslander DALBY. March 2. Mixed, Very. At the Dalby Police Court, on March 2, Thomas Skelly, police constable of Taroom station, was charged with having unlawfully beaten and wounded John Clune, thereby causing the said John Clune grievous bodily harm. Prosecutor deposed: l am barman at the Tattersall's Hotel in Drayton-street; on the 8th February, I was sitting in the parlor of the above house, at about 2 o'clock in the morning, in company with Donald McLaran; the doors were locked; the prisoner forced the side door open into the sitting-room, and rushed in, in a very excited manner, and said he wanted drinks; I told him it was near daylight on Sunday, and he couldn't have any; he said he didn't care a … what the hour was, he would have them; after walking round the table three times, he stood opposite the door by which he had entered; I begged him for heaven's sake to leave the place, I didn't want to have anything to say to him; there is a step from the floor of the room to the verandah outside, about 8 to 12 inches high. As he stood on the step, he struck me a blow on the forehead with some instrument that I believe from the feel of it to have been iron; I fell on my knees, and he caught me by the coat and vest, pulling them partly over my head, and dragged me through the door on the verandah outside, and struck me on the head with some weapon, and on the cheek-bone, on the side of my head, on the left arm, and gave me several blows on the body; I heard McLaren say, “You wretch, are you going to murder the old man?” Immediately after, I heard McLaren say, “I've got the … waddy from him,” or words to the same effect; I reported the matter to the Chief constable, and then went to Dr. Howlin; I am still under medical treatment on account of the injuries I received." Some other evidence corroboratory of that given by Clune having been taken, the prisoner made a statement in defence: "That he was returning from a friend's house, and meeting with Cohen outside Tattersall's Hotel, asked him to have a drink. Having entered the parlor he asked Clune, who was sitting with McLaren on the sofa, for two drinks. Clune said “You … deceitful wretch I'll not serve you.” Said to Clune, "If you will not serve me don't insult me." Clune said, “You… deceitful dog if you don't go out I'll put you out.” Replied, “I'll go out without being put out.” As I was standing by the door, Clune jumped off the sofa and struck me; he kept striking me into the street. He tore my coat and scarf; I was held by McLaren whilst Clune beat me. I called out to McLaren, “Are you going to hold me while he breaks my face?” I released myself and went away. I said, “Remember Mr Clune, for the language you've used, I'll summon you on Monday morning.” I would have stopped but that I had orders to return to my station at Taroom as quickly as possible." Committed for trial at the next District Court sitting, April 27. Bail allowed, £200 and two of £100 each. |

27 Apr 1874 Skelly's trial was held in the morning

2 May 1874 Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser

WESTERN DISTRICT COURT Monday Apr 27

The court opened this morning. His Honor Judge Blakeney presided. Mr. Hely, Crown Prosecutor, attended to conduct the criminal business, of which there was a larger amount than has, for some time, fallen to our share, there being two cases of aggravated assault, both charged against Police Constables; two cases of cattle stealing; one of attempted suicide; two of larceny, besides another of larceny in which no bill had been found, and two prisoners in this case were consequently discharged.

Constable Thomas Skelly - charges of aggravated assault.

Jas (SIC - it should have been "Thomas") Skelly, a police constable of Taroom station, was indicted for having on Sunday morning, the 8th Feb last, assaulted and beaten John Clune, thereby causing him, the said John Clune, bodily harm. A second count charged the accused with an aggravated assault.

Mr. May of Toowoomba defended the prisoner. A jury was empannelled, consisting of Messrs. Herbert Evans (Foreman), Allan McDonald, Thos. Norris, Jas. Conroy, Jas. Laverecombe, John Birch, Jas. Hall, L. Freeney, M. Fogarty, John Cran, Jas. Ryan and John Ashmore.

The Crown Prosecutor stated, the case, which was that on Sunday morning Feb 8, at about two o'clock, the accused entered the parlor where prosecutor and Donald McLaren were sitting, having forced open the door, which had been locked, and asked for drinks. Being refused by Clune, he walked about the room in a very excited manner, and on Clune's putting his hand on him to put him out, struck Clune in the forehead with the butt end (metal) of a whip which he carried. Seizing Clune by the coat, he dragged him outside the door on to the verandah, and pulled Clune’s coat over his head, continuing to beat him over the body with the butt of the whip, until McLaren, going to Clune’s help, seized the whip and took it from him. McLaren having given Skelly back his whip, he went away and Clune went to the Police Station, and thence to Dr. Howlin, who dressed the wound in Clune’s forehead. The wound was of so serious a nature, that for some days the patient's life was in danger, as erysipelas might supervene, and he was under medical treatment until the 13th of March. These were the facts, and the C.P. proceeded to call his witnesses.

John Clune repeated his evidence given by him at the Police Court, and published in the Dalby Herald of March 7; and Mr. May, of Toowoomba, for the defence, failed to shake his testimony in any important particular.

Donald McLaren’s evidence was the same as that he gave one examination referred to; and his cross-examination had the same result as in the former case.

Dr. Howlin spoke as before reported, of the dangerous nature of the wound from which he had apprehended danger for about a week. Being cross-examined by Mr. May, he acknowledged that such a wound might have been caused by Clune’s falling with forehead on a hard or sharp stone.

This closed the case for the Crown, and Mr. May, proceeded to call his witness for the defence; and, Adolphus Cohen, being sworn and examined by Mr. May, said: I opened the door, Skelly followed; I went in first; Skelly asked for two drinks; Clune said " You … deceitful dog if you don't go out I’ll kick you out,” he said those words again; Skelly said "I'll go out without your putting me out;” Clune laid hold of him and pushed him out; the door closed, both going outside; after a minute or two I opened the door and went out, McLaren following me; I saw them both striking one another, Skelly with a whip, Clune with his fists; I called to McLaren not to hold Skelly while Clune hit him; McLaren let go and they catched hold of each other again; Clune fell; I had been in the house before; about 2 or 3 minutes had elapsed before I returned with Skelly.

Mr Hely asked whether the witness was not a Jew, and the witness replied that he was.

Mr. Hely also asked whether it was not usual for Jews to be sworn on the Old Testament with their hats on.

The witness said it was, but he considered the oath taken by him as binding on his conscience.

McLaren recalled, in answer to the Crown Prosecutor, said, he did not hold Skelly while Clune hit him; Clune could not hit Skelly; the fight was all on one side; If Clune hit him at all he must have hit very low.

By Mr. May: I gave the whip a drag to get it away; I took him unawares and caught his hand; I have been told he was a police constable, but I did not know it at the time.

This closed the evidence, and Mr. May proceeded to remark on the great discrepancies between the evidence of Clune and McLaren, and that of the witness Cohen; The former two had evidently not well rehearsed their story together; the assault, if it could be called an assault, was committed on Skelly by Clune; a fight took place and the wound on Clune's head might have been caused by his falling against the fence or on a stone. He claimed an acquittal for his client.

The Crown Prosecutor in reply, said that discrepancies on minor points did not show collusion; on the contrary, they were a sign of truth. No two persons would relate a circumstance alike in all respects. Had the two witnesses agreed to a story, they would have made no difference in the minor particulars. Clune’s memory was no doubt so affected at the time that he forgot many of the accompanying circumstances. Clune was justified in expelling Skelly. McLaren saw a blow struck with the whip which caused the wound. If in expelling Skelly, Clune used more violence than was necessary, he would become the aggressor. The facts of the case proved the first count, but if the jury were not convinced, they could find a verdict on the second, or of common assault.

His Honor summed up, directing the jury to confine their attention to a common assault. The discrepancy in the evidence was most extraordinary. Clune swore positively that no one but Skelly came in. How can his evidence be believed. What, from previous action, would be likely to be Clune’s part against Skelly. In his account of the assault he is contradicted by his own witness. He denies Cohen’s presence altogether. Clune's evidence was very contradictory. If the jury had any doubt, they were to give the prisoner the benefit of it.

The jury retired, and in about half an hour returned, finding the prisoner "NOT GUILTY!"

Editorial comment by The Dalby Herald

The evidence of the witness Cohen as above, presents so remarkable a contrast to that given by him at the examination at the Police Court, March 2, before the Police Magistrate and Mr Skelton, that we subjoin the former statement:-

Cohen called by prisoner and sworn said in answer to questions asked by him, "I remember meeting you on Saturday night Feb. 7th or early on Sunday morning Feb. 8th; you asked me to have a drink at Clune’s; I said, it is of no use going, Clune will not serve us; you said, "Oh never mind he won't know me;" I went with you into the small parlor; you asked Clune for drinks; he said; "It is after hours, I won't serve you;” Clune opened the door and pushed you through; he did not strike you but you struck him and knocked him down; you were not knocked down by Clune, but you knocked him down and tore his coat in two pieces; You said you had lost your scarf, and I went back and got it for you; I did not tell Constable Walsh that Clune was in fault for striking and knocking you down first; you did not speak to me at that time of summoning Clune; you said "I'll get your licence dismissed altogether now.” This was at the time of the row.

By the Bench: I saw the whip at the time but will not swear to it; the one produced is like it, but I think it was longer; prisoner held the thin end in his hand, and struck Clune with the thick end; he struck him several times; McLaren pulled him off and I pulled Clune away, and called Mrs. Clune to attend to him; prisoner had the whip in his hands; I lost sight of the whip whilst I was attending to Clune, and McLaren might have taken the whip and given it back without my seeing it.

2 May 1874 Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser

WESTERN DISTRICT COURT Monday Apr 27

The court opened this morning. His Honor Judge Blakeney presided. Mr. Hely, Crown Prosecutor, attended to conduct the criminal business, of which there was a larger amount than has, for some time, fallen to our share, there being two cases of aggravated assault, both charged against Police Constables; two cases of cattle stealing; one of attempted suicide; two of larceny, besides another of larceny in which no bill had been found, and two prisoners in this case were consequently discharged.

Constable Thomas Skelly - charges of aggravated assault.

Jas (SIC - it should have been "Thomas") Skelly, a police constable of Taroom station, was indicted for having on Sunday morning, the 8th Feb last, assaulted and beaten John Clune, thereby causing him, the said John Clune, bodily harm. A second count charged the accused with an aggravated assault.

Mr. May of Toowoomba defended the prisoner. A jury was empannelled, consisting of Messrs. Herbert Evans (Foreman), Allan McDonald, Thos. Norris, Jas. Conroy, Jas. Laverecombe, John Birch, Jas. Hall, L. Freeney, M. Fogarty, John Cran, Jas. Ryan and John Ashmore.

The Crown Prosecutor stated, the case, which was that on Sunday morning Feb 8, at about two o'clock, the accused entered the parlor where prosecutor and Donald McLaren were sitting, having forced open the door, which had been locked, and asked for drinks. Being refused by Clune, he walked about the room in a very excited manner, and on Clune's putting his hand on him to put him out, struck Clune in the forehead with the butt end (metal) of a whip which he carried. Seizing Clune by the coat, he dragged him outside the door on to the verandah, and pulled Clune’s coat over his head, continuing to beat him over the body with the butt of the whip, until McLaren, going to Clune’s help, seized the whip and took it from him. McLaren having given Skelly back his whip, he went away and Clune went to the Police Station, and thence to Dr. Howlin, who dressed the wound in Clune’s forehead. The wound was of so serious a nature, that for some days the patient's life was in danger, as erysipelas might supervene, and he was under medical treatment until the 13th of March. These were the facts, and the C.P. proceeded to call his witnesses.

John Clune repeated his evidence given by him at the Police Court, and published in the Dalby Herald of March 7; and Mr. May, of Toowoomba, for the defence, failed to shake his testimony in any important particular.

Donald McLaren’s evidence was the same as that he gave one examination referred to; and his cross-examination had the same result as in the former case.

Dr. Howlin spoke as before reported, of the dangerous nature of the wound from which he had apprehended danger for about a week. Being cross-examined by Mr. May, he acknowledged that such a wound might have been caused by Clune’s falling with forehead on a hard or sharp stone.

This closed the case for the Crown, and Mr. May, proceeded to call his witness for the defence; and, Adolphus Cohen, being sworn and examined by Mr. May, said: I opened the door, Skelly followed; I went in first; Skelly asked for two drinks; Clune said " You … deceitful dog if you don't go out I’ll kick you out,” he said those words again; Skelly said "I'll go out without your putting me out;” Clune laid hold of him and pushed him out; the door closed, both going outside; after a minute or two I opened the door and went out, McLaren following me; I saw them both striking one another, Skelly with a whip, Clune with his fists; I called to McLaren not to hold Skelly while Clune hit him; McLaren let go and they catched hold of each other again; Clune fell; I had been in the house before; about 2 or 3 minutes had elapsed before I returned with Skelly.

Mr Hely asked whether the witness was not a Jew, and the witness replied that he was.

Mr. Hely also asked whether it was not usual for Jews to be sworn on the Old Testament with their hats on.

The witness said it was, but he considered the oath taken by him as binding on his conscience.

McLaren recalled, in answer to the Crown Prosecutor, said, he did not hold Skelly while Clune hit him; Clune could not hit Skelly; the fight was all on one side; If Clune hit him at all he must have hit very low.

By Mr. May: I gave the whip a drag to get it away; I took him unawares and caught his hand; I have been told he was a police constable, but I did not know it at the time.

This closed the evidence, and Mr. May proceeded to remark on the great discrepancies between the evidence of Clune and McLaren, and that of the witness Cohen; The former two had evidently not well rehearsed their story together; the assault, if it could be called an assault, was committed on Skelly by Clune; a fight took place and the wound on Clune's head might have been caused by his falling against the fence or on a stone. He claimed an acquittal for his client.

The Crown Prosecutor in reply, said that discrepancies on minor points did not show collusion; on the contrary, they were a sign of truth. No two persons would relate a circumstance alike in all respects. Had the two witnesses agreed to a story, they would have made no difference in the minor particulars. Clune’s memory was no doubt so affected at the time that he forgot many of the accompanying circumstances. Clune was justified in expelling Skelly. McLaren saw a blow struck with the whip which caused the wound. If in expelling Skelly, Clune used more violence than was necessary, he would become the aggressor. The facts of the case proved the first count, but if the jury were not convinced, they could find a verdict on the second, or of common assault.

His Honor summed up, directing the jury to confine their attention to a common assault. The discrepancy in the evidence was most extraordinary. Clune swore positively that no one but Skelly came in. How can his evidence be believed. What, from previous action, would be likely to be Clune’s part against Skelly. In his account of the assault he is contradicted by his own witness. He denies Cohen’s presence altogether. Clune's evidence was very contradictory. If the jury had any doubt, they were to give the prisoner the benefit of it.

The jury retired, and in about half an hour returned, finding the prisoner "NOT GUILTY!"

Editorial comment by The Dalby Herald

The evidence of the witness Cohen as above, presents so remarkable a contrast to that given by him at the examination at the Police Court, March 2, before the Police Magistrate and Mr Skelton, that we subjoin the former statement:-

Cohen called by prisoner and sworn said in answer to questions asked by him, "I remember meeting you on Saturday night Feb. 7th or early on Sunday morning Feb. 8th; you asked me to have a drink at Clune’s; I said, it is of no use going, Clune will not serve us; you said, "Oh never mind he won't know me;" I went with you into the small parlor; you asked Clune for drinks; he said; "It is after hours, I won't serve you;” Clune opened the door and pushed you through; he did not strike you but you struck him and knocked him down; you were not knocked down by Clune, but you knocked him down and tore his coat in two pieces; You said you had lost your scarf, and I went back and got it for you; I did not tell Constable Walsh that Clune was in fault for striking and knocking you down first; you did not speak to me at that time of summoning Clune; you said "I'll get your licence dismissed altogether now.” This was at the time of the row.

By the Bench: I saw the whip at the time but will not swear to it; the one produced is like it, but I think it was longer; prisoner held the thin end in his hand, and struck Clune with the thick end; he struck him several times; McLaren pulled him off and I pulled Clune away, and called Mrs. Clune to attend to him; prisoner had the whip in his hands; I lost sight of the whip whilst I was attending to Clune, and McLaren might have taken the whip and given it back without my seeing it.

Skelly Trial: Questions and (possible) Answers

Q1.Did Clune know Skelly was a policeman?

A1. Yes. Clune ran the Tattersalls Hotel in Roma before coming to Dalby. He would have been aware of Skelly and his heavy drinking reputation as he was stationed in nearby Taroom.

Q2. Who was Adolphous Cohen and why did he change the evidence he offered at the committal hearing?

A2. Cohen ran a watchmaking and jewellery shop 2 doors from Tattersall Hotel. It seems likely he was induced by threats or bribes to change his evidence to be supportive of Constable Skelly. The Dalby Herald was amazed by the change in evidence and hence published Cohen's original evidence for all to read.

Q3. Why did the jury find Constable Skelly not guilty of assault?

A3. One suspects the jury was bribed or perceived an advantage may be had by supporting the police force. They certainly displayed no loyalty or affection towards John Clune.

Q4. What sort of a policeman was Constable Thomas Skelly and what became of him?

A4. Thomas Skelly had a very long and colourful career in the Queensland Police Force between 1872 and 1902. He was described by his superiors as a "growling man" who needed constant supervision. He was excellent on a horse, apparently. Stationed at Leyburn, Roma, Rockhampton, The Leap near Mackay and Townsville, alcohol dependence hampered Skelly's career and he was finally promoted to Acting Sergeant in 1902. He retired due to ill health soon after on a full pension.

Late one night in Townsville 1907, Skelly (60) was shot in the leg by Michael McKee (68). Skelly was estranged from his family - his wife Mary (42) who ran the Queens Arms Hotel, and their grown up daughter. He was standing on a low stump outside the bedroom window and kissing Mary when he was shot. McKee initially gave the excuse that in the dark he thought he was aiming his shotgun at a prowler, but later confessed. There were 40 letters written by Skelly to Mary over a three year period in his possession (she had kept them under the mattress) and had previously warned him to stay away from his wife. He said he shot to wound, not to kill. He claimed Skelly was a serial adulterer who had ruined three marriages.

Skelly's leg was amputated but he succumbed to complications and Michael McKee's charge of unlawful wounding was upgraded to unlawful killing. Before he died, Skelly said he had no business being where he was on that night and he did not wish to prosecute Michael McKee.

The jury concluded that Skelly died of "gangrene arising from carelessness on his own part in dressing and washing the wound prior to being removed to hospital" and for not seeking medical assistance earlier. They found McKee not guilty, despite the judge warning that irrespective of Skelly's self-administered treatment and ill health, if McKee fired the shot then he was guilty of manslaughter at the very least. The judge said he did not agree with the jury but sympathised with their decision.

In a will drawn up in hospital, 2 days before he died, Skelly nominated Mary McKee as his major beneficiary and donated £20 to his local church for "masses for the repose of my soul" ..... His estate of over £400 included an insurance payout of over £250. This would have helped support Mary McKee and her 5 children for some years.

Mary McKee was arrested for drunken behaviour in 1913 and died in 1918. She had been missing several days (not an unusual event, said the family) before her body was found in a lagoon. She was pre-deceased by Michael McKee in 1916.

Q5. Is there any connection between the McLaran family and any of the jurors?

A5. Juror Jas. Ryan (d. 1914) may have been the father of James Ryan (1869 - 1945). James married Donald McLaran's niece, Catherine Jane Milford (1872 - 1970). Warning: THIS may be INCORRECT.

Q1.Did Clune know Skelly was a policeman?

A1. Yes. Clune ran the Tattersalls Hotel in Roma before coming to Dalby. He would have been aware of Skelly and his heavy drinking reputation as he was stationed in nearby Taroom.

Q2. Who was Adolphous Cohen and why did he change the evidence he offered at the committal hearing?

A2. Cohen ran a watchmaking and jewellery shop 2 doors from Tattersall Hotel. It seems likely he was induced by threats or bribes to change his evidence to be supportive of Constable Skelly. The Dalby Herald was amazed by the change in evidence and hence published Cohen's original evidence for all to read.

Q3. Why did the jury find Constable Skelly not guilty of assault?

A3. One suspects the jury was bribed or perceived an advantage may be had by supporting the police force. They certainly displayed no loyalty or affection towards John Clune.

Q4. What sort of a policeman was Constable Thomas Skelly and what became of him?

A4. Thomas Skelly had a very long and colourful career in the Queensland Police Force between 1872 and 1902. He was described by his superiors as a "growling man" who needed constant supervision. He was excellent on a horse, apparently. Stationed at Leyburn, Roma, Rockhampton, The Leap near Mackay and Townsville, alcohol dependence hampered Skelly's career and he was finally promoted to Acting Sergeant in 1902. He retired due to ill health soon after on a full pension.

Late one night in Townsville 1907, Skelly (60) was shot in the leg by Michael McKee (68). Skelly was estranged from his family - his wife Mary (42) who ran the Queens Arms Hotel, and their grown up daughter. He was standing on a low stump outside the bedroom window and kissing Mary when he was shot. McKee initially gave the excuse that in the dark he thought he was aiming his shotgun at a prowler, but later confessed. There were 40 letters written by Skelly to Mary over a three year period in his possession (she had kept them under the mattress) and had previously warned him to stay away from his wife. He said he shot to wound, not to kill. He claimed Skelly was a serial adulterer who had ruined three marriages.

Skelly's leg was amputated but he succumbed to complications and Michael McKee's charge of unlawful wounding was upgraded to unlawful killing. Before he died, Skelly said he had no business being where he was on that night and he did not wish to prosecute Michael McKee.

The jury concluded that Skelly died of "gangrene arising from carelessness on his own part in dressing and washing the wound prior to being removed to hospital" and for not seeking medical assistance earlier. They found McKee not guilty, despite the judge warning that irrespective of Skelly's self-administered treatment and ill health, if McKee fired the shot then he was guilty of manslaughter at the very least. The judge said he did not agree with the jury but sympathised with their decision.

In a will drawn up in hospital, 2 days before he died, Skelly nominated Mary McKee as his major beneficiary and donated £20 to his local church for "masses for the repose of my soul" ..... His estate of over £400 included an insurance payout of over £250. This would have helped support Mary McKee and her 5 children for some years.

Mary McKee was arrested for drunken behaviour in 1913 and died in 1918. She had been missing several days (not an unusual event, said the family) before her body was found in a lagoon. She was pre-deceased by Michael McKee in 1916.

Q5. Is there any connection between the McLaran family and any of the jurors?

A5. Juror Jas. Ryan (d. 1914) may have been the father of James Ryan (1869 - 1945). James married Donald McLaran's niece, Catherine Jane Milford (1872 - 1970). Warning: THIS may be INCORRECT.

27 Apr 1874 Balfour's trial was held in the afternoon

2 May 1874 Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser

On the reassembling of the Court at 2 PM, James Balfour, a police constable was charged with having assaulted and beaten William Dockrill, thereby occasioning him, the said William Dockrill of bodily harm. A second count charged the defendant with an aggravated assault.

The jury in this case consisted of Messrs. Faulkner (Foreman), Thos. Norris, Allan McDonald, D. Morgan, W. Driver, Jas. Clarke, P. Wormwell, J. Sweeny, L. Byrne, P. Moy, Thos. McGoldrick and J. Birch.

Mr. May defended the prisoner.

The Crown - Prosecutor opened the case. It appeared that on 21st February the prisoner came to Dockrill’s place and asked for the paper of Returns. He afterwards asked to be allowed to put his horse in the paddock. Dockrill consented but the prisoner, who was in uniform, objected to put the horse in the horse paddock, and insisted on putting it into a small paddock kept by Mr. Dockrill for his calves and lambs; Dockrill refused to allow him; prisoner asked if it was it a freehold, and Dockrill replying that it was not, prisoner said a Government officer could put his horse where he liked. Dockrill said that if he did, he (Dockrill) would turn him out again, on which prisoner replied, "If you touch my horse, you'll never touch another as long as you live”; Dockrill still objecting, prisoner struck him a blow on the cheek bone with the butt end of a hammer-headed whip which he had in his hand and a second blow behind the ear. This dropped him (Dockrill) on his knees, and putting up his hands to guard his head he received other blows on his arms, but managed to catch the whip in his hands and wrest it from prisoner, going into the house with it. The prisoner followed, saying he would not go until he got his whip. It was given to him and he went away.

(The whip was produced in Court. It was about 2ft. 6in. long, with a metal hammer at the end, weighing about 10 ounces.)

These were the facts of the case, which were proved by Dockrill who gave his evidence, the same as that at the Police Court, February 27.

By Mr. Hely: The prisoner came while I was at tea; he asked for the Annual Returns. He said he would stop that night and put his horse in the paddock. (Witness’ further evidence confirmed the statement made by the Crown Prosecutor.) I said you're drunk, go away; he appeared to be drunk.

By Mr. May, for prisoner: I came into town a distance of 85 miles, two or three days afterwards; I gave him back his whip as I wished to get rid of him; I do not remember having seen him before; I cannot say whether he struck with the right or left hand; I did not go into the house and ask for my gun.

By Mr. Hely: I can not remember all that took place, he gave me no time.

Adam Black: Was at Dockrill’s house, Feb. 21, and saw prisoner there; afterwards saw him and Dockrill together, Dockrill was stooping down and prisoner standing over him. I came out as I heard someone cry out; I saw the prisoner with a whip like the one produced in his hands. I saw one blow struck which Dockrill warded off with his hands and caught hold of the whip after a struggle. Mrs. Dockrill came out and got between them. Dockrill went inside; prisoner went to the back door and asked for his whip, which Dockrill gave him.

By Mr. May: I believe the weapon to have been a whip; it was not a broomstick; prisoner asked Dockrill whether it was freehold property; after that he struck him; he left next morning; heard Dockrill tell prisoner he was drunk; didn't know whether there was any place to obtain liquor nearer than 18 miles by the way prisoner came.

By Mr. Hely: He called Dockrill a stingy, miserable wretch.

By Mr. May : Dockrill asked for his gun; we would not let him have it.

The Crown Prosecutor and Mr. May declining to address the jury, His Honor said the Bench of Magistrates would have been fully justified in dealing with this case. This differed from the last, as there was no imputation on any of the witnesses. A squatter or selector had a perfect right to his grass. This was a most wanton and unprovoked attack. Because a man was clothed with a little brief authority, did he suppose he could put his horse where he liked? If he pleased he might put it in the garden! On Dockrill’s objecting, he struck him a blow which might have fractured his skull, and because he, Dockrill, under this aggravation, asks for his gun, Mr. May asks for an acquittal. It was a clear case, without any cause. No private person's house would be safe if such acts were tolerated.

The jury retired, and in about an hour returned, giving a verdict of NOT GUILTY!!!

His Honor asked Sergeant Keane whether the man was still in the police, and on the Sergeant answering that he was, "Then," said His Honor, "I shall make it my business when I return to Brisbane to see the Commissioner and have the force relieved of his presence. He is a most dangerous man and will bring disgrace on you all. The Police Force is generally a most useful and efficient body of men."

2 May 1874 Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser

On the reassembling of the Court at 2 PM, James Balfour, a police constable was charged with having assaulted and beaten William Dockrill, thereby occasioning him, the said William Dockrill of bodily harm. A second count charged the defendant with an aggravated assault.

The jury in this case consisted of Messrs. Faulkner (Foreman), Thos. Norris, Allan McDonald, D. Morgan, W. Driver, Jas. Clarke, P. Wormwell, J. Sweeny, L. Byrne, P. Moy, Thos. McGoldrick and J. Birch.

Mr. May defended the prisoner.

The Crown - Prosecutor opened the case. It appeared that on 21st February the prisoner came to Dockrill’s place and asked for the paper of Returns. He afterwards asked to be allowed to put his horse in the paddock. Dockrill consented but the prisoner, who was in uniform, objected to put the horse in the horse paddock, and insisted on putting it into a small paddock kept by Mr. Dockrill for his calves and lambs; Dockrill refused to allow him; prisoner asked if it was it a freehold, and Dockrill replying that it was not, prisoner said a Government officer could put his horse where he liked. Dockrill said that if he did, he (Dockrill) would turn him out again, on which prisoner replied, "If you touch my horse, you'll never touch another as long as you live”; Dockrill still objecting, prisoner struck him a blow on the cheek bone with the butt end of a hammer-headed whip which he had in his hand and a second blow behind the ear. This dropped him (Dockrill) on his knees, and putting up his hands to guard his head he received other blows on his arms, but managed to catch the whip in his hands and wrest it from prisoner, going into the house with it. The prisoner followed, saying he would not go until he got his whip. It was given to him and he went away.

(The whip was produced in Court. It was about 2ft. 6in. long, with a metal hammer at the end, weighing about 10 ounces.)

These were the facts of the case, which were proved by Dockrill who gave his evidence, the same as that at the Police Court, February 27.

By Mr. Hely: The prisoner came while I was at tea; he asked for the Annual Returns. He said he would stop that night and put his horse in the paddock. (Witness’ further evidence confirmed the statement made by the Crown Prosecutor.) I said you're drunk, go away; he appeared to be drunk.

By Mr. May, for prisoner: I came into town a distance of 85 miles, two or three days afterwards; I gave him back his whip as I wished to get rid of him; I do not remember having seen him before; I cannot say whether he struck with the right or left hand; I did not go into the house and ask for my gun.

By Mr. Hely: I can not remember all that took place, he gave me no time.

Adam Black: Was at Dockrill’s house, Feb. 21, and saw prisoner there; afterwards saw him and Dockrill together, Dockrill was stooping down and prisoner standing over him. I came out as I heard someone cry out; I saw the prisoner with a whip like the one produced in his hands. I saw one blow struck which Dockrill warded off with his hands and caught hold of the whip after a struggle. Mrs. Dockrill came out and got between them. Dockrill went inside; prisoner went to the back door and asked for his whip, which Dockrill gave him.

By Mr. May: I believe the weapon to have been a whip; it was not a broomstick; prisoner asked Dockrill whether it was freehold property; after that he struck him; he left next morning; heard Dockrill tell prisoner he was drunk; didn't know whether there was any place to obtain liquor nearer than 18 miles by the way prisoner came.

By Mr. Hely: He called Dockrill a stingy, miserable wretch.

By Mr. May : Dockrill asked for his gun; we would not let him have it.

The Crown Prosecutor and Mr. May declining to address the jury, His Honor said the Bench of Magistrates would have been fully justified in dealing with this case. This differed from the last, as there was no imputation on any of the witnesses. A squatter or selector had a perfect right to his grass. This was a most wanton and unprovoked attack. Because a man was clothed with a little brief authority, did he suppose he could put his horse where he liked? If he pleased he might put it in the garden! On Dockrill’s objecting, he struck him a blow which might have fractured his skull, and because he, Dockrill, under this aggravation, asks for his gun, Mr. May asks for an acquittal. It was a clear case, without any cause. No private person's house would be safe if such acts were tolerated.

The jury retired, and in about an hour returned, giving a verdict of NOT GUILTY!!!

His Honor asked Sergeant Keane whether the man was still in the police, and on the Sergeant answering that he was, "Then," said His Honor, "I shall make it my business when I return to Brisbane to see the Commissioner and have the force relieved of his presence. He is a most dangerous man and will bring disgrace on you all. The Police Force is generally a most useful and efficient body of men."

Balfour Trial: Questions and (possible) Answers

Q1.Why did the jury find Constable Balfour not guilty of assault?

A1. As in Skelly's trial, it is a mystery why a jury of seemingly reasonable men would find Balfour not guilty. Perhaps the jury was bribed or perceived an advantage may be had by supporting the police force. Perhaps the jury were prejudiced against squatters. The judge certainly did not agree with the jury's decision.

Q2. Were there any long term repercussions from this case?

A2. William Dockrill held a grudge against the police force for many years, as this 1887 incident was the result:

A curious case came before Mr. Pinnock*, at the Brisbane Police Court, on Wednesday last. It appears that Constable Burke was a passenger by train to Brisbane some days previously. He placed his helmet on a seat near another passenger, and, soon after leaving Laidley, he missed his headgear. He interrogated defendant, whose only reply was that he had "done a constable before now." Burke thereupon arrested him, and, although he was not violent, marched him to the Brisbane lockup with handcuffs on. The defendant, whose name turns out to be Dockrill, is one of the oldest squatters on the Darling Downs; and an inquiry will probably be held.

* Mr Pinnock was responsible for the 1868 inquest into the death of Jane McLaran.

Q3. Is there any chance William Dockrill met Donald McLaran on this occasion?

A3. This was the only entertainment in Dalby on this day. It is highly likely that the two aggrieved men sat through their very similar cases and later discussed the events of the day. Donald (40) may have even discovered that William Dockrill (44) had an 18 year old niece living on his property at Tartha. This may have been the seminal day in our family history.

Q4. Did these two trials (and the 1877 incident of "Donald's Lost Watch") reveal any traits that Donald McLaran and William Dockrill had in common?

A4. Yes - neither man would ever take a backward step when wronged.

Q1.Why did the jury find Constable Balfour not guilty of assault?

A1. As in Skelly's trial, it is a mystery why a jury of seemingly reasonable men would find Balfour not guilty. Perhaps the jury was bribed or perceived an advantage may be had by supporting the police force. Perhaps the jury were prejudiced against squatters. The judge certainly did not agree with the jury's decision.

Q2. Were there any long term repercussions from this case?

A2. William Dockrill held a grudge against the police force for many years, as this 1887 incident was the result:

A curious case came before Mr. Pinnock*, at the Brisbane Police Court, on Wednesday last. It appears that Constable Burke was a passenger by train to Brisbane some days previously. He placed his helmet on a seat near another passenger, and, soon after leaving Laidley, he missed his headgear. He interrogated defendant, whose only reply was that he had "done a constable before now." Burke thereupon arrested him, and, although he was not violent, marched him to the Brisbane lockup with handcuffs on. The defendant, whose name turns out to be Dockrill, is one of the oldest squatters on the Darling Downs; and an inquiry will probably be held.

* Mr Pinnock was responsible for the 1868 inquest into the death of Jane McLaran.

Q3. Is there any chance William Dockrill met Donald McLaran on this occasion?

A3. This was the only entertainment in Dalby on this day. It is highly likely that the two aggrieved men sat through their very similar cases and later discussed the events of the day. Donald (40) may have even discovered that William Dockrill (44) had an 18 year old niece living on his property at Tartha. This may have been the seminal day in our family history.

Q4. Did these two trials (and the 1877 incident of "Donald's Lost Watch") reveal any traits that Donald McLaran and William Dockrill had in common?

A4. Yes - neither man would ever take a backward step when wronged.

Donald McLaran patronised the hotels of Dalby throughout his life.

Malcolm Lewis McLaran, had this musical toby jug as a reminder of his father.

Malcolm Lewis McLaran, had this musical toby jug as a reminder of his father.